Abstract

Our understanding of gender roles within society is rapidly changing. These changes are in conflict with our traditional beliefs in the West that men are fundamentally masculine and that women are fundamentally feminine, which has caused a gender imbalance in which there are few women in positions of power.

With ?Design Thinking? becoming more and more prevalent, the mindset of the whole industry is shifting from one that is mostly analytically focussed, to one that is sympathetic to the needs of the users. My hypothesis is that Design Thinking stems from the theory that androgynous people are more creative, and it is offering a way for people in traditional, masculine business roles to be more considerate of the end user. Through thorough research into the psychological and sociological aspects of gender, and how they relate to Design Thinking, I will suggest a theory for a successful design process. I will also argue that traditional gender assumptions are damaging to the productivity of the design industry.

The solution that I propose is that designers should move away from traditional gender roles, and into more flexible roles, if they wish to create successful products that come from a mix of analytical and sympathetic thinking. To prove the hypothesis, I will look at Design Thinking and its parallels with gender theory, based on empirical evidence and historical analysis. I believe that a widespread adoption of Design Thinking, and a better understanding of gender theory, will help designers create better products, which in turn will have a huge influence on society.

Intro

The common view in Western society is that masculinity and femininity are fundamentally separate, but there are theories that these genders are constructs rather that biological truths (Bem, 1974) (Perry, et al., 1992). To understand the gender binaries, it is necessary to understand its past, and how society begin restructuring itself into a patriarchal system (Hartmann, 1976). Much of Western history is dominated by men, and their long-term control over societal hierarchies has normalised a labour division between men and women (Hartmann, 1976). Masculinity has allowed these men to be more ambitious and to think more analytically, leading them to pioneer the Industrial Revolution through a scientific process that lacked empathy (Thompson, 1963) (Hartmann, 1976).

However, the Scientific Revolution that came beforehand would not have happened were it not for the more feminine attitude of some 16th Century scientists (Harari, 2014). Femininity in leaders has since been proven to foster innovation (Kark, et al., 2012), yet we still design in a primarily masculine way, and so the industry is still occupied mostly by men (Women's Engineering Society, 2018) (Fortune, 2019). As a result, women are more likely to work in jobs considered to be feminine (Kark, et al., 2012) (Garlick, 2004). This phenomenon is a continuation of patriarchy, which is causing a large inequality of the sexes (Hartmann, 1976).

The purpose of this dissertation is to make sense of gender theory and discuss its benefits when utilised in design practice. Empirical evidence is referenced to prove that patriarchy still exists, and that it has a negative effect on men and women by pressuring them to fulfil traditional gender roles.

Western Gender

According to Merriam-Webster, masculinity is defined as ?the quality or nature of the male sex? and femininity is defined as ?the quality or nature of the female sex? (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). These qualities vary from culture to culture, and so for the sake of this dissertation masculinity will be considered as traits that are historically associated with the male sex, and femininity as traits that are historically associated with the female sex. Masculinity and femininity will be referred to as genders, members of the male sex as ?men?, and members of the female sex as ?women?.

Masculinity and femininity can be measured on the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI), which was devised by American psychologist Sandra Bem in 1974. Bem proves that ?masculinity and femininity are logically and empirically independent.? (Davies, n.d.). It is important to note that these results reflect the Western view of gender and may not be applicable to other cultures. It is also important to note that these views do change over time. As Hartmann explains in Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex, ?the lines of division between masculine and feminine is constantly shifting? (Hartmann, 1976).

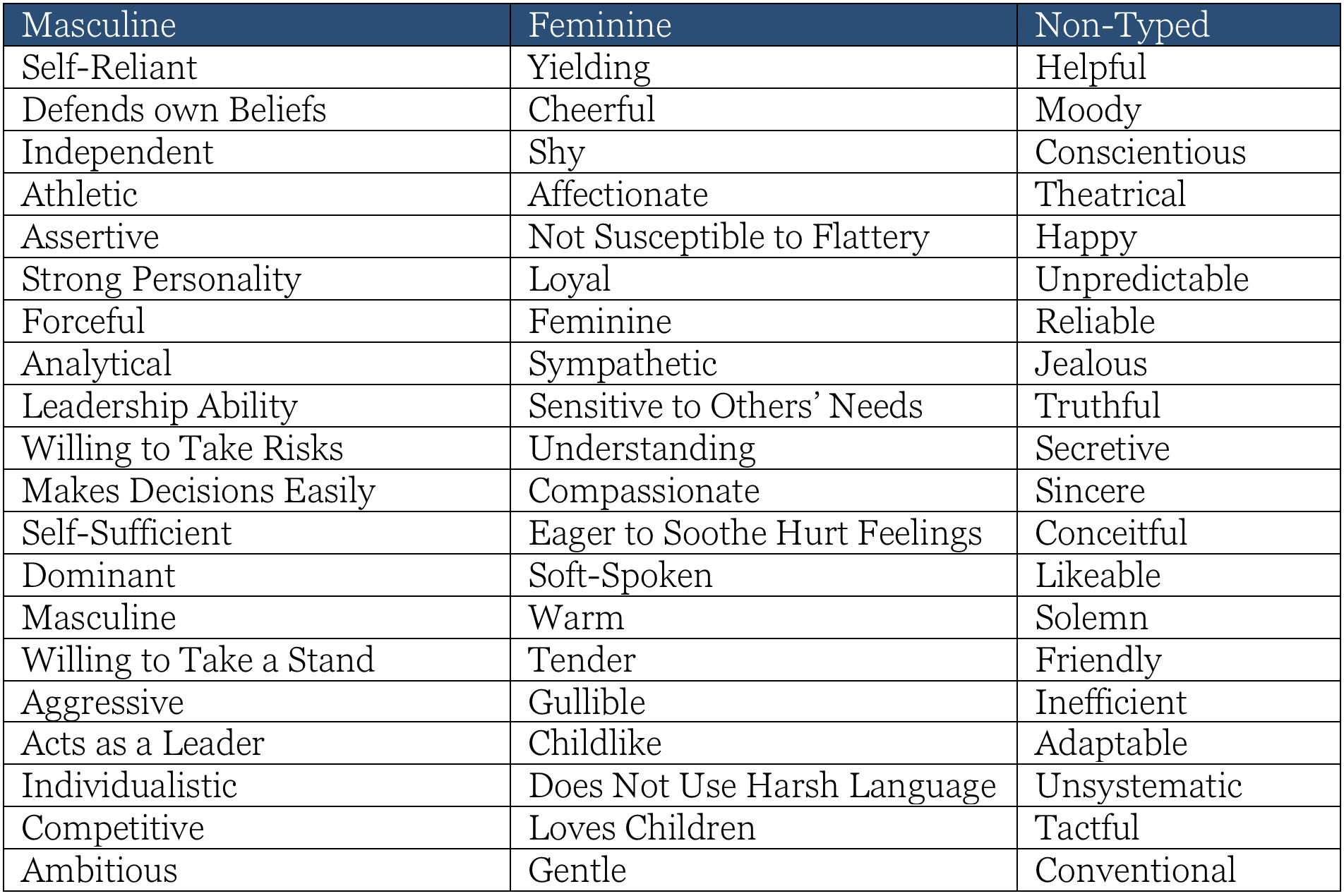

Table 1: BSRI Evaluation Chart. Source: S. Bem

The BSRI traits can be found in the chart above. A person who rates themselves higher in the masculine traits than the feminine traits would be described as ?Masculine?, and a person who rates themselves higher for feminine traits than masculine traits would be described as ?Feminine?. ?Non-typed? traits do not give any indication of a person?s gender and can be found in masculine and feminine people.

As we can see from the chart, there is a clear distinction between masculinity and femininity. By using only terms from the BSRI, masculine people tend to be dominant, ambitious people with an analytical mindset, and feminine people tend to be shy, yielding people with a sympathetic mindset. As Bem concisely puts it, ?masculinity has been associated with an instrumental orientation, a cognitive focus on "getting the job done"; and femininity has been associated with an expressive orientation, an affective concern for the welfare of others? (Bem, 1974).

This method for gender trait evaluation has been questioned by Perry et al., who have suggested that though this may be a fairly accurate test of how we perceive social desirability in others, it does not necessarily mean that we would use these terms to describe ourselves (Perry, et al., 1992). For this dissertation, BSRI is assumed to be accurate, at least for evaluating stereotypical gender traits in Westerners.

Historical Influence of Gender Traits on Men and Women

Patriarchy in the West is a widely discussed topic, and can be described as "a system of social structures and practices in which men dominate, oppress, and exploit women" (Giddens & Griffiths, 2006). Patriarchy is a social structure that has existed for possibly 6000 years, argues Kraemer (Kraemer, 1991) though it is hard to say exactly how prevalent patriarchy is in the Western world. This dissertation will focus on patriarchy in Western, capitalist countries, where the majority of the design industry is.

So how did this patriarchy come about? Hartmann argues that in Capitalist society ?the hierarchical domestic division of labor is perpetuated by the labor market, and vice versa? (Hartmann, 1976). Hartmann explains that this cycle occurs because low wages ensure that women are reliant on men, since they are encouraged to marry. This puts pressure on women to fulfil domestic chores for the family. However, this did not happen by chance; Hartmann argues that capitalist men maintain their positions of power by ?segmenting the labor market?, which began with their existing skills in the hierarchy building (Hartmann, 1976). Hartmann also analyses various theories on the anthropological aspect of patriarchy but concludes that we can?t yet prove whether or not it came about for biological reasons. She mentions examples of cultures where women have more authority than men, such as the !Kung tribe (Hartmann, 1976).

It is apparent that the division of labour has been normalised to such an extent that we now expect a division in all areas of the lives of men and women. The wide differences in gender traits could be a result of the separation of men from any feminine traits, and women from any masculine traits. Men, who have been in dominant, leading roles for much of Western history, have come to understand these traits as an undeniable part of being male. As sociologist Theodore Caplow put it, ?the adult male group is to a large extent engaged in a reaction against feminine influence? (Caplow, 1954). As the BSRI concludes, we still believe that ?Dominance? and ?Leadership Ability? are traits of masculinity and so, historically, they are traits of men (Bem, 1974).

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th Century was pioneered by men. These men, as designers of products, factories, and even whole working communities, often ignored the wellbeing of their workers. They would frequently employ children to work the machines. British historian E. P. Thompson wrote that ?the exploitation of little children, on this scale and with this intensity, was one of the most shameful events in our history? (Thompson, 1963). Women were also exploited during this time, as their jobs were ?lower paid, considered less skilled, and often involved less exercise of authority or control? (Hartmann, 1976). Eventually, as improvements in children?s rights meant they spent less time in the factories, it was necessary for one of the parents to stay at home; the patriarchal nature of the time meant that it was men who continued to earn money, whilst the women lost their authority over the family (Hartmann, 1976) (Thompson, 1963).

This is in contrast to pre-industrialisation life where much of society was organised into guilds. Men and women were active workers in the guilds, therefore neither parent could afford to take time off work to focus on the development of their children. These children developed as apprentices instead, working from a young age for the guild. As such, all members of society had more equal roles, though higher skilled jobs were still reserved for men (Hartmann, 1976).

It could well be the masculine mindset of the pioneering men of the industrial revolution that allowed them to think more analytically - and in terms of what would create the highest revenue ? rather than what would be best for the wellbeing of the workers. They were indeed successful in creating a revolution, and in advancing technology tremendously, but it was at the expense of women?s rights. It is clear that the men in power acted more in their own self-interest due to their masculine personalities.

Although it may seem that the majority of past innovations were spearheaded by masculine minds, we can find examples of it being a feminine mindset that allowed for change. Harari argues that the rapid development of science and technology of the Scientific Revolution of the 16th Century was in fact ?a revolution of ignorance? (Harari, 2014). Harari explains how during this time, science was born because of scientists? willingness to learn and to accept that they were wrong (Harari, 2014). This could be interpreted as a childishness; a willingness to yield and to learn, which are in turn feminine traits on the BSRI chart (Bem, 1974). The historic masculinity of people in power could be a reason why this revolution took such a long time to come about. Though it was masculine men who profited from the Scientific Revolution, it was not necessarily a masculine mindset that allowed these changes to occur. Thus, if femininity is beneficial to opening us up to new ideas, and to innovate through inquisitiveness rather than to gain power, it could be a desirable trait for all innovators.

With children now spending much of their time in school, the argument that women should stay at home to care for them is not relevant. Therefore, we would expect equal numbers of men and women in high-paying jobs in positions of power. However, professions that require higher levels of analytical thinking, and are generally seen as ?serious? occupations, still have significantly higher numbers of male workers. In 2018, only 12.37% of engineers in the UK were female. Only 25.4% of British females aged 16-18 plan on having a career in engineering, as opposed to 51.9% of males in the same age range. (Women's Engineering Society, 2018). Similarly, there are very few women in CEO positions. In the 2019 Fortune 500 list, which evaluates the revenue of the 500 highest-earning CEOs in the United States, only 6.6% of the CEO positions were held by women (Fortune, 2019).

Since there is no clear physical or mental barrier for women to study engineering or become CEOs, it is plausible that the low number of women in these sectors is accounted for by assumed gender roles. Both these professions involve a very masculine mindset; engineering is a particularly analytical field, and CEOs require leadership ability, dominance, and ambition. All of these are defined by the BSRI as masculine traits (Bem, 1974). Is a predominantly masculine personality bad for innovation? A focus on the technical aspects of, and the wealth generated from, our designs could distract us from the user-level implications. It is easy to not consider the fate of the workers and users when you don?t allow yourself to empathise with them.

If women are not taking up these analytical jobs, then where are they? Hartmann points out that many women have ended up in domestic roles, with their husbands working in more serious jobs (Hartmann, 1976). Many find themselves in feminine jobs, such as art. Garlick, argues that art is seen as feminine, and that working on art is ?often regarded as a frivolous activity, as something belonging to the sphere of leisure or play, and thus as not being a properly ?manly? concern? (Garlick, 2004). This assumption is echoed somewhat by Perry et al., who found that feminine individuals were perceived as people who would enjoy low intensity jobs such as being a florist or librarian (Perry, et al., 1992). A comparison can be made with the BSRI system, where ?Childlike? is seen as a feminine trait, which can be considered as playfulness (Bem, 1974). However, we should not be so quick to demonise playfulness. Schaefer, the ?father of play therapy?, believes that play has traditionally been seen as a ?trivial or childish pursuit?, but that more recently playfulness is increasingly being seen as a sign of good mental health (Schaefer, 2003). There is nothing inherently wrong with feminine traits, but by confining feminine people to roles such as art, we are essentially reinforcing the segregation of the sexes.

Androgyny in Design

Design is a relatively new field. How is it different? As Don Norman puts it in the Design of Everyday Things, "design is concerned with how things work, how they are controlled, and the nature of the interaction between people and technology? (Norman, 1988). Design, therefore, is the relationship between the masculine side of how things work and technology, and the feminine, empathetic side of its interaction with people.

So far, this dissertation has concentrated on historical entrepreneurs, not designers. This is because there are very few examples of individuals or companies in the past that concerned themselves with the interaction between their products and the users. There was therefore a prevalence of ?masculine design?. The contemporary design mentality is different in that it allows us to move beyond the constraints of an analytical and apathetic design approach. Combining traits of both genders might allow us to design better products by thinking in non-traditional ways. Designers can learn to listen to their users, to be sympathetic to their needs, and then use these insights to develop a well-rounded product that is socially sustainable, economically viable and physically durable.

Designs that exhibit both, or neither, traits are sometimes called agender, gender-fluid, genderless, or unisex. In terms of the BSRI scale, those who rate highly for masculine and feminine traits would be described as ?androgynous? (Bem, 1974). Merriam-Webster also defines ?the quality or state of being neither specifically feminine or masculine? (Merriam-Webster, n.d.) as androgyny, therefore it will be referred to as ?androgyny? or ?androgynous? for the purpose of this dissertation.

To better understand androgyny, and how it can be advantageous to the whole design process, it is necessary to look at androgynous designs. Designers of industrial and digital products, fashion, and architecture are the creators of much of popular culture and so have the ability to sway society. A design tends to reflect the ethos of its designer, therefore insights on androgynous designers can be found through analysis of androgynous products.

A clear way for a consumer to express their gender identity is through fashion, and many examples of gender-expressive designs can be found in this field. Writing about androgynous fashion, culture journalist Charlotte Gush asks ?what is fashion, if not the promise that you may create yourself, however you see fit?? (Gush, 2016). Could fashion be the first genre to allow consumers to express their personal flavour of androgyny, without having to adhere to traditional gender roles?

One influential figure who brought androgynous fashion into the spotlight was David Bowie, who has been dubbed by fashion historian Colin McDowell as the ?father of androgyny? (Business of Fashion, 2018). His gender-free stage personas, which sometimes included a ?man-dress?, have influenced many fashion designers, including Jean Paul Gaultier and Vivienne Westwood (Business of Fashion, 2018). This was an important turning point for the acceptance of androgyny; all of the examples that I have listed below have happened since Bowie?s initial androgynous appearances in the 1970s, and we can see a movement of companies that are committing to ?breaking the binary? (Gush, 2016).

Figure 1: David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust. Source: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns

These days, women?s wardrobes will often include many masculine menswear garments. In contrast, men tend to adhere to ?conventionally masculine styles? (Gush, 2016). This is in accordance with Caplow?s assertion that men tend to reject all feminine influence (Caplow, 1954). It could be that women, with less pressure to be overtly feminine, have been more willing to display masculine traits.

There is another theory, however, that menswear has made its way into women?s lives through workwear and sportwear, which are being sold to women ?to enhance their corporeal mobility? (Smith & Greig, 2003). This could indicate that this acceptance of masculine clothing has in fact been an effort to allow women to fit in better in the more masculine environment of business, and not a general acceptance of non-traditional clothing. There is evidence of masculine qualities being beneficial for women in research by Kark et al., where it was proven that a mix of gender traits in leaders allowed them to inspire innovation in their companies through transformational leadership (Kark, et al., 2012).

It is interesting to note that, in marketing for women?s and men?s suits, there is often a wide distinction in how the two are presented. In Figure 2, a man is shown as being serious, with a precise tie and shoes. The woman, in contrast, is shown as being more open and fun, with an open collar and more flamboyant and colourful footwear. It seems that the fashion industry is selling women?s suits as more fun, open and feminine versions of the traditional male suit, rather than creating equal clothing for both, and that this approach is reinforcing gender separation in traditionally masculine roles.

Figure 2: Women?s and Men?s tailored suits, by sister companies Sumissura and Hockerty. Sources: Sumissura.com (website), Hockerty.com (website)

However, the clear definitions of gender boundaries are slowly dissipating, with there now being a ?clear movement across youth culture toward a more androgynous mix? (Gush, 2016). This change can be seen as a societal shift towards acceptance of feminine traits, a movement which I will refer to as feminism. Since youth culture is becoming more accepting of androgyny, those young people that become designers will carry this androgynous mindset with them, making it likely that we will see design continuing to become more androgynous in the future.

In Japan, for example, a ?humorous, kitsch, androgynous style? has evolved (Kinsella, 1995). This appears to be in conjunction with Minimalism, a style which has had a big effect on contemporary design. Minimalism owes much of its ideology to Zen Buddhism which ?instils a desire for simplicity? and has deep roots in Japanese culture (Shamsian, 2018). Both minimalist design and androgynous design aim to reach a wider audience by removing any elements of the product that only appeal to specific groups of people.

Minimalism and androgyny can be found in many popular Japanese brands such as Muji, an abbreviation for Mujirushi Ry?hin, or ?No-Brand Quality Goods?. The company?s ethos is to create designs that do not need designer labels to improve their appeal. They simply create what they call ?basic? products. As Tanaka Ikko, Muji?s Chief advisor, explains: ?You may feel embarrassed if the person sitting next to you on the train is wearing the same clothes as you. If they are jeans, however, you wouldn't be worried, because jeans are what we could describe as ?basic? clothing. All Muji products are such ?basic? products'' (Holloway & Hones, 2007). This minimalism can be found all across Muji?s range of products.

In 2019 Muji released an androgynous range of clothing as part of their Labo project, with clothing for men, women and non-binary genders, as well as being ?suitable for all body types? (Moor, 2019), as seen in Figure 3. This is a clear signal that Muji are working towards an all-inclusive future where home products, furniture, and clothing are available to all. It is probable that this ethos will affect the Western design world significantly, since Muji are a respected brand amongst designers, and, with 328 stores worldwide, their androgynous products reach a large audience.

Figure 3: Muji Labo. Source: muji.com (website)

There are also examples of androgynous clothing making its way into the West. In 2015, Selfridges opened a pop-up store called ?Agender?, in the hope of creating a ?genderless shopping experience? (Tsjeng, 2015). It has been called revolutionary in the way in which it was a space where ?men and women could shop for clothes irrespective of gender distinction? (Clark & Rossi, 2019). Linda Hewson, Selfridges? Creative Director, explained that they ?could feel a cultural/societal shift coming and wanted to connect to and embrace its impact in a way that's unique to Selfridges? (Gush, 2016). This shows how there is already an interest ? though perhaps not a great demand just yet, given the few examples available ? in gender-free clothing. By adopting this progressive idea, these influential companies are ensuring that consumers can start to direct the design industry through their buying decisions.

Unfortunately for designers, they cannot sell a product unless there is a demand. One example of design that tends to be heavily gendered is children?s products, due to the desires of the parents that buy the products. The use of blue and pink to denote boys and girls respectively is a relatively new phenomenon. In fact, at one point this was reversed, and ?pink was considered more of a boy?s color? (Frassanito & Pettorini, 2008), therefore it would be fair to assume that these colours have been set by society, rather than by biology. Even so, they are a good indicator for how gendered a design is and changing tastes in children?s products reveal a lot about the beliefs of parents.

The popular minimalist furniture brand IKEA design particularly androgynously. On their website they define their approach as ?Democratic Design?, ?because we believe good home furnishing is for everyone? (IKEA, 2016). This all-inclusive approach does not reinforce gender norms and is a clear indication that there is already a market for ungendered products. Figure 4, from IKEA?s website, makes no mention of gender and combines the masculine elements of precision with its geometric workspace, and the feminine elements of warm, childish colours and playful, surreal toys.

Figure 4: Ikea, ?Small bedroom ideas for teens?. Source: Ikea.com (website)

Design Thinking

IKEA are not the first to employ a democratic form of thinking about design; there are many forms, commonly referred to as Design Thinking. In modern-day businesses, a consideration for the human aspect of products is becoming equally as important as the economics and engineering. Design Thinking combines analytical and psychological knowledge to create successful, sustainable products.

This new mentality towards innovation was promoted in the 1980s by American innovator Buckminster Fuller, who called for a ?design science revolution' ?based on science, technology and rationalism,? to address the societal and environmental problems that he believed could not be resolved by politics and economics (Cross, n.d.). One of the first design consultancies to implement this ?design science revolution? in the form of Design Thinking was IDEO. Their CEO, and Northumbria University graduate, Tim Brown describes it as ?a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer's toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success? (Brown, 2020).

This is exactly the mentality that Fuller was recommending, and we can see this mentality as a combination of the feminine aspects of a human-centred, empathic approach, and the masculine aspects of the technological and business-minded approach. Thus, Design Thinking could be thought of as Androgynous Thinking; a designer that can successfully use Design Thinking must also be able to use their full range of personality traits. Traditionally, the masculine and feminine aspects of design have been split up; there are engineers and leaders who push their own ideas, and there are psychologists and researchers who strive to understand the needs of the users. But even though both genders can be found in organisations, the boss?s mentality tends to be more masculine, since this allows them to channel their efforts into leading the team and making sure that the company and products are financially sound. This can be observed in the BSRI; how can a leader lead without ambition or leadership ability? Though perhaps a better research question would be: Can opening ourselves up to an androgynous mindset be beneficial for everyone, or just those who work in creative roles?

There are many that believe that Design Thinking has aided writers, artists, musicians, engineers, businesses and even scientists in innovating (Interaction Design Foundation, 2020). This can be a confusing idea if we think of design in the traditional sense; the creation of physical products. However, if we define design as problem solving then it might begin to make sense. Design Thinking is then the methodology that we use to effectively solve problems, and so it could also be named ?Androgynous Problem Solving?. Many leading contemporary design courses have begun to teach Design Thinking, including MIT; Stanford; Harvard and d.school (Interaction Design Foundation, 2020), and its adoption by design academics would signal that it is an effective, or at least promising, mindset.

How can Design Thinking be measured quantitively? Most research has been qualitative, though one recent study found that an established Design Thinking practice within an organisation can achieve a Return on Investment between 71-107% (Ryan Hart, 2019). This shows that in terms of monetary gain at least, Design Thinking is effective. Further research needs to be undertaken to fully understand the benefits, therefore conclusions must be drawn from other sources at present.

The creative benefits of Design Thinking could be accounted for by the androgynous mindset. According to a study on the link between gender groups and creativity, androgenic participants scored higher on creativity and creative attitude (Norlander, et al., 2000). This signals that a combination of masculine and feminine traits is beneficial to creative work, and so more androgynous individuals would thrive in the creative industry. Kark et al. (2012) suggest that the mindset also aids in transformational leadership, which can be useful for designers that lead multidisciplinary groups.

Despite all of the promise of Design Thinking, it has not been adopted particularly quickly into established companies. The start-up culture that has emerged in Silicon Valley shows an apparent rejection of traditional masculine traits in men, though paradoxically it is still a mostly male culture, dubbed the ?Valley of the Boys? in interviews of male computer science employees by Cooper (Cooper, 2000). Cooper describes the Silicon Valley men as people who had been marginalised as children for being ?nerds?; an insult that suggests that they are not masculine enough to take part in men?s activities, making them inferior. To prove that they are not inferior, they decided to launch a technological revolution (Cooper, 2000).

Cooper notes that though the work itself is gender-neutral, there are certain emphases that make it more masculine or feminine. Cooper?s participants do not define themselves as masculine, though interestingly they still exhibit many masculine traits. There is an alternative form of masculinity in Silicon Valley that serves to prove one?s commitment to a team, through making their long exhausting hours clear to other team members. This is similar to the exhaustion men would show after working in manual labour jobs. Physical strength has always been the main biological advantage of men over women and so it makes sense that this would be one of the prime pillars of masculinity. This is a quality that Willis (1977) recognised in working class men, observing that ?difficult, uncomfortable or dangerous conditions are seen, not for themselves, but for their appropriateness to a masculine readiness and hardiness?. Thus, though they reject traditional masculinity, and they are working in conditions that are vastly different to labouring men, their mentality that the work is difficult and therefore ?virtuous? suggests that this is, in fact, a masked form of masculinity.

This alternative masculinity still serves the same purpose; Cooper quotes Connel?s definition of hegemonic masculinity as the ?configuration of gender practices which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of legitimacy of patriarchy? (Connell, 1995). Thus, the male dominance of Silicon Valley can be explained by the fact that the male culture is still very strong, even though their masculinity is non-traditional. The men do show an egalitarian gender ideology, such as rejecting bureaucratic company structures to allow for more open communication and creativity, and even going to great lengths to hire more women. However, in practice it is still a male culture that dominates the industry. This was also found to be true by Kark et al. (2012). According to Connell, the specific traits the hegemonic men exhibit are irrelevant; there are ?multiple masculinities? that come about for a number of reasons, but still leave men in positions of authority. Thus, even though Silicon Valley champions the ideology of Design Thinking, the area?s ingrained gender beliefs continue to stifle gender equality.

Summary

There is no doubt that we still live in a patriarchal society, which has oppressed women by its implementation over millennia. Whether or not it came about for biological reasons, we cannot say. There are examples of matriarchal cultures, which would suggest that patriarchy is not the only way that society can be organised.

The patriarchal divide of the sexes has ensured that dominant, masculine traits have been firmly associated with men, and submissive, feminine traits with women. This, in turn, has led to an excess of masculine thinking in intellectual roles, which prioritises revenue and numerical perfection over worker and customer satisfaction. Studies have discovered that masculinity and femininity are not permanently linked to our sex, with some suggesting that there are many benefits to being androgynous, such as aiding with transformational leadership, creativity, and general wellbeing. There are past examples of feminine traits opening up masculine innovators? minds to new ideas, such as with the birth of science. Though masculine behaviours prevail in authoritative roles they are not inherently negative. Masculinity can allow managers and designers to be strong, ambitious leaders. The issue is that a one-sided, binary gender constrains our ability to think both analytically and empathetically; to lead when it is needed, and to yield when it is not.

A look at fashion suggests that there has been a large shift in our perceptions of androgyny since the 1970s. With prominent androgynous figures such as Bowie, society has started to accept non-binary genders as being equal to traditional gender norms. Masculine clothing is becoming more common in women?s wardrobes, showing an acceptance of women?s masculine side. Suits, which were once a male-only garment, are now very common attires for women in more masculine, business roles. They are marketed differently to women than to men, however, with men?s suits being shown as purely masculine, and women?s suits shown as being more androgynous ? masculine clothing on a feminine personality. Muji have released a range of genderless clothing in recent years, showing a very current trend in the acceptance of androgyny among consumers. This democratic mindset could have originated in Japanese minimalism, though it is now becoming global with minimalist furniture companies such as IKEA pioneering a ?Democratic Design? philosophy.

Fuller was one of the first to call for a Design Thinking revolution in the 1980s, and this mentality has since been adopted by many prominent design consultancies, as well as design schools, across the globe. Design Thinking can also be attributed to many innovations in creative and business fields, and so it is clear that the mentality can be effective for a successful work ethic. Design Thinking, androgynous thinking, and minimalism show a lot of cross-over, and it seems likely that they are promoting the same idea of an all-inclusive design process for an all-inclusive audience.

Despite all the evidence, and despite the best efforts of many companies, patriarchy still exists, albeit in an obscured form. It is now normal for women to be given equal opportunities to apply for masculine roles, but the strong male culture within these companies makes it difficult for them to feel comfortable and accepted. This has led to large numbers of men in authoritative roles, and large numbers of women in roles with fewer responsibilities. Even in more progressive areas ? such as in Silicon Valley ? companies are finding it difficult to employ more women due to the strength of the male culture.

Conclusion

Society is unquestionably moving towards a more androgynous form of thinking and expression. It is impossible to predict how quickly this transition will happen. The West?s learnt biases ensure that any widespread change will take generations; it is only recently that the younger generations have begun to adopt this progressive attitude. Many influential companies are taking steps to design for this new market, helped by their adoption of Design Thinking. As more companies adopt this philosophy, it should aid them in creating products that foster healthy biases in consumers, and to change the internal biases of many businesses. This would reverse a strong tendency for exclusive male cultures to arise, to the detriment of good design.

Over time there may well be a diminution of patriarchy, but only if we all take meaningful steps towards promoting all-inclusive androgynous attitudes in today?s youth. A world without patriarchy would be one where men and women do not have to choose between masculinity and femininity; it is one where men can feel comfortable being playful and yielding, where women can feel comfortable being leaders and domineering, without any societal pressure for them to confine themselves to a small section of their full personality. A more androgynous world would balance out the wage gap between men and women and could lead to the end of oppression on women, greatly improving the living quality of women. It would be a positive step if all leaders and designers used androgynous thinking when faced with societal and environmental problems, where past mindsets have often been overly analytical or overly compassionate.

Bibliography

Bem, S., 1974. THE MEASUREMENT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ANDROGYNY, s.l.: Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

Brian A. Primack, M., 2017. https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(17)30016-8/fulltext, s.l.: s.n.

Brown, T., 2020. Design Thinking. [Online] Available at: https://www.ideou.com/pages/design-thinking [Accessed January 2020].

Business of Fashion, 2018. Fashion History: David Bowie and the Birth of Androgyny. [Online] Available at: https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/education/fashion-history-david-bowie-and-the-birth-of-androgyny [Accessed 19 January 2020].

Caplow, T., 1954. The Sociology of Work. New York: s.n.

Clark, H. & Rossi, L.-M., 2019. Clothes (Un)Make the (Wo)Man ? Ungendering Fashion (2015)?. s.l.:Intellect Books.

Connell, R., 1995. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Connell, R. W., 1987. Gender and Power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cooper, M., 2000. Being the ?Go-To Guy?: Fatherhood, Masculinity, and the Organization of Work in Silicon Valley. Qualitative Sociology, Volume 23, pp. 379-405.

Cross, N., n.d. Designerly ways of knowing: design discipline versus design science (2001). s.l.:Design Issues.

Cupchik, G. C., 1983. The Scientific Study of Artist Creativity, s.l.: The MIT Press.

Davies, S. N., n.d. Bem Sex-Role Inventory. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/Bem-Sex-Role-Inventory

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020. Industrial Revolution. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution [Accessed January 2020].

Fortune, 2019. Fortune 500. [Online] Available at: https://fortune.com/fortune500/ [Accessed 5 December 2019].

Frassanito, P. & Pettorini, B., 2008. Pink and blue: the color of gender. Child's Nervous System volume 24, Volume 24, p. 881?882.

Fukusawa, N., 2018. Naoto Fukasawa: Embodiment. s.l.:Phaidon.

Garlick, D. S., 2004. Distinctly Feminine: On the Relationship Between Men and Art, s.l.: Berkeley Journal of Sociology.

Giddens, A. & Griffiths, S., 2006. Sociology. 5th Edition ed. s.l.:Polity Press.

Gush, C., 2016. the binary is boring: moving towards a genderless fashion future. [Online] Available at: https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/7xbqyq/the-binary-is-boring-moving-towards-a-genderless-fashion-future [Accessed 19 January 2020].

Harari, Y. N., 2014. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. 1st Edition ed. s.l.:Harvill Secker.

Hartmann, H., 1976. Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex. Signs, pp. 137-169.

Holloway, J. & Hones, S., 2007. Muji, materiality, and mundane geographies. Environment and Planning, pp. 555-69.

IKEA, 2016. Democratic Design. [Online] Available at: https://www.ikea.com/ms/en_JP/this-is-ikea/democratic-design/ [Accessed 19 January 2020].

Interaction Design Foundation, 2020. What is Design Thinking and Why Is It So Popular?. [Online] Available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/what-is-design-thinking-and-why-is-it-so-popular [Accessed 20 January 2020].

Kraemer, S., 1991. The Origins of Fatherhood: An Ancient Family Process. s.l.:s.n.

Moor, L., 2019. MUJI Labo Launches Genderless Clothing Line for Spring/Summer 2019. [Online] Available at: https://www.tokyoweekender.com/2019/02/muji-labo-launches-genderless-clothing-line-for-springsummer-2019/ [Accessed 19 January 2020].

Norlander, T., Erixon, A. & Archer, T., 2000. PSYCHOLOGICAL ANDROGYNY AND CREATIVITY: DYNAMICS OF GENDER-ROLE AND PERSONALITY TRAIT, s.l.: Scientific Journal Publishers.

Norman, D., 1988. The Design of Everyday Things. s.l.:Basic Books.

Ryan Hart, B. B., 2019. The ROI Of Design Thinking, s.l.: Forrester.

Schaefer, C. E., 2003. Play Therapy with Adults. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Shamsian, J., 2018. Inside Japan's incredibly minimalist homes. [Online] Available at: https://www.insider.com/inside-japans-extremely-minimalist-homes-2016-6

Smith, C. & Greig, C., 2003. Women in Pants: Manly Maidens, Cowgirls, and Other Renegades. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc..

Thompson, E. P., 1963. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: s.n.

Tsjeng, Z., 2015. Inside Selfridge?s radical, gender-neutral department store. [Online] Available at: http://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/24088/1/inside-selfridges-radical-gender-neutral-department-store [Accessed January 2020].

Willis, P., 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. New York: Columbia University Press.

Women's Engineering Society, 2018. Useful Statistics. [Online] Available at: https://www.wes.org.uk/content/wesstatistics

Year

2020Type

research, theory, essay,Feeling lucky? Click me for a random idea!

© Owen Pickering 2022